Everything is so bad. Pieces of news keep cracking my brain open all over again; this week, it was Brad Lander’s forceful and unjust arrest by ICE. On Instagram, I keep seeing that awful quote that’s often misattributed to Stalin (lmao): “One death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic.” It’s giving “African proverb!” I think believing in this makes you a psychopath? I’m partially basing that off that my old startup boss, who was a lunatic, said this to me once.

I am not alone in feeling useless at best, inherently complicit at worst. I pay taxes and I walk around enjoying art and sensations, all of which feels so fucked. The alarms are going off and I have the absolute luxuries of “contemplation” and “complaint.” Blah blah, no one likes handwringing. There’s nothing else to do, for me, I think, than relish what I’m afforded and try to help those who can’t.

What I know: There’s no sense in denying our humanity. That’s when we lose. It doesn’t help that I’m suspended in the most emotional bout of PMS I’ve ever experienced and everything is making me cry. What’s new? I cried last week at this brilliant George Saunders essay about AI and art (below) and was reminded that I don’t need to box up all my love and put it away until things “get better.” This isn’t a justification so much as it is a plea. Amid all the ugliness, don’t forget the parts of you that are lovely. Especially don’t forget the parts of other people that are, too.

1. “I Doubt the Machine Because the Machine Is Not You” by George Saunders

Unsurprisingly, George Saunders on AI and its potential use in fiction is an incredible read that confirmed so many things I feel and think about what it means to create art. The entire essay is worth your time and I had a hard time pulling just one paragraph to embed here, but the one below might be my favorite (emphasis my own):

So, to me, even the best AI is going to forfeit, from the get-go, the very thing that we turn to art for. We want to be briefly in the hands of someone who is giving us, based on her experience, a new way in which we might look at the world. It’s not the right way, but it’s her way, and we try it on, in part to be reminded that our way is just our way; that any way of looking at the world is partial and subjective.

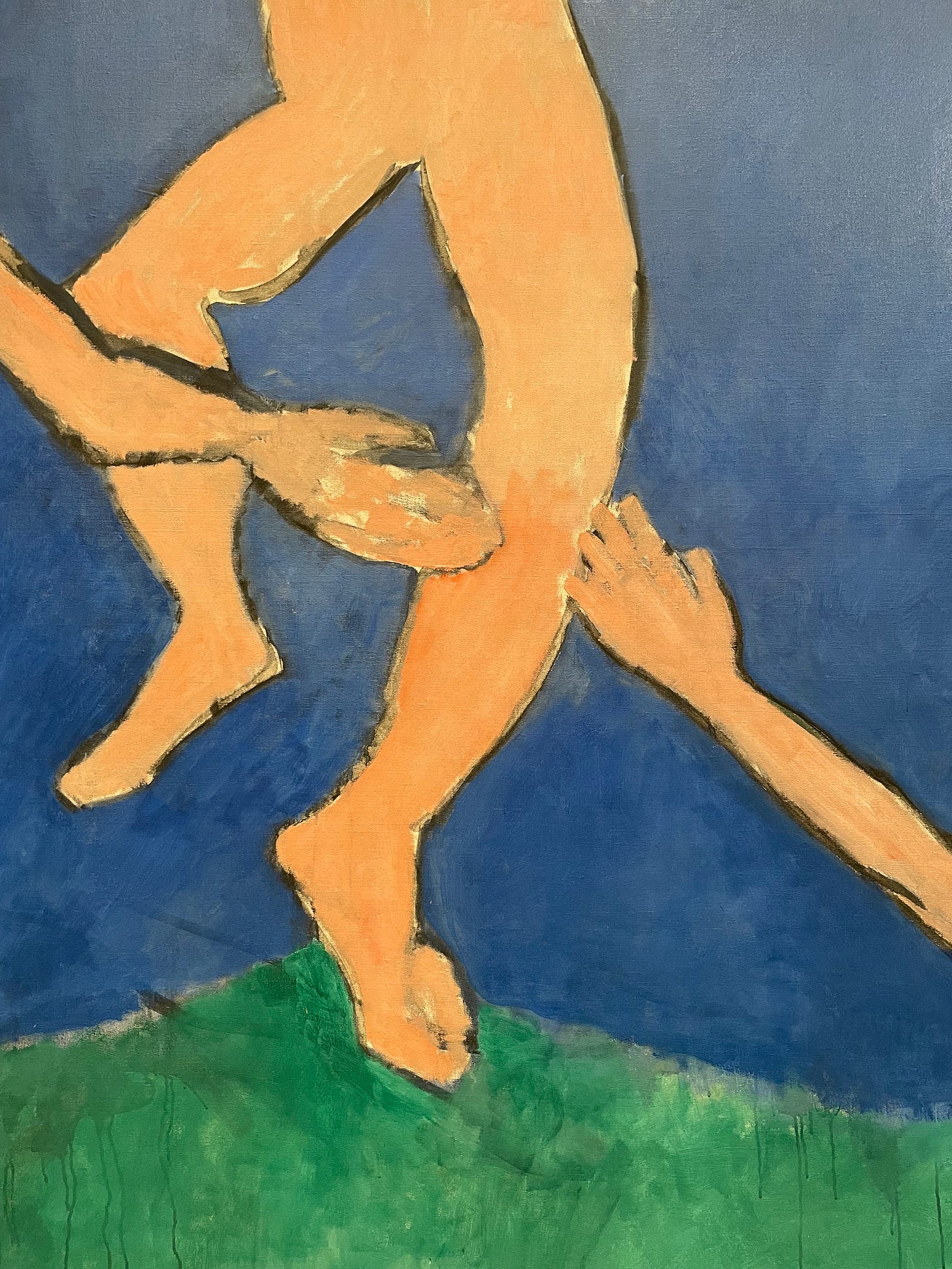

I love that because it’s true, and because it makes me think of Marshall and his photography. He takes pictures, mostly, of people, which makes this even more interesting. When you look at one of his photos, like this one:

What you’re seeing is not just two men standing together on the north side of Barton Springs, but a compilation of every experience Marshall has ever had, every person he’s ever seen, every splash of pool water he’s ever felt, every everything he’s ever held. That’s what makes this photograph so beautiful; that’s what makes this photograph art. Reach through the screen, reach all the way through the photo, and what you poke on the other side is Marshall’s brain, life, and feelings. I’m in love with his brain and so I love his work. I don’t know that I could ever love someone and not love their work. Not really. Not in the way I experience now.

Saunders isn’t the first writer to distill the experience of art in this way. His essay reminds me of another essay I love by Alexander Chee.

2. “On Becoming an American Writer” by Alexander Chee

In his AI essay, Saunders talks about the idea of a fence in fiction. He writes:

Part of the reason we keep reading a story is the sense that, over there on the other side of the fence, is a very smart presence who has consented to play a game with us – it is creating expectations, becoming aware of the expectations it is creating, rewarding some of them, subverting others, and so on, and all of this is happening in a very intimate human space – the space of the shared experience the reader and writer co-inhabit, of both having roamed this earth in human bodies.

In “On Becoming an American Writer,” first published in 2018 by The Paris Review and, at full length, in Chee’s collection How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, he also writes about this make-believe fence:

To write is to sell a ticket to escape, not from the truth but into it. My job is to make something happen in a space barely larger than the span of your hand, behind your eyes, distilled out of all that I have carried, from friends, teachers, people met on planes, people I have seen only in my mind, all my mother and father ever did, every favorite book, until it meets and distills from you, the reader, something out of the everything it finds in you. All of this meets along the edge of a sentence like this one, as if the sentence is a fence, with you on one side and me on the other.

Chee’s essay, prescient more and more, grapples with the existential question of art’s place in a failed state. Which is kind of what Saunders gets at in his essay—both writers are ultimately questioning whether art is a legitimate use of time in a world where atrocities are happening and where data centers can “generate” “it” within seconds.

I can’t pretend to have the answer to that. But I do know that my life and outlook have been irrevocably changed, and for the better, by the art I’ve been afforded. I know I’ve been handed access to lives and perspectives that have shaped me, broken me open, expanded me. Art isn’t the only way, but it is one way.

3. “In Defense of Despair” by Hanif Abdurraqib

I already recommended this essay here once, but I’m sharing it again with all of this in mind. I’m struck by so much in this essay, but this section in particular:

I often consider the flexibility of language, in a very literal, unpoetic sense. Its uses are pleasureful, treacherous, devastating. For example: I am writing about the beauty of sunlight and the sight of my beloved dog’s face in the same language that a Department of Homeland Security head uses to call for more rapid and “efficient” deportations, an “Amazon Prime for Human Beings.” When it comes to horrors given shape through the functions of language, even this does not haunt me as much as a press conference held by children in Gaza in 2023, during which they pleaded in English for the world to protect them, despite the world’s prolonged and ongoing failure to answer that call. Language fails at the feet of an empire’s violence; language fails to scale the ever-growing wall between who is and isn’t deemed worthy of a life. Yet I am trying to use this same failing machinery to communicate how, for the sake of my own fragile heart, and sometimes fragile brain, I remain more committed to honesty than I do to optimism.

Also, Abdurraqib on Brian Wilson is a must:

On that note…

4. Surf’s Up by the Beach Boys

We lost both Brian Wilson and Sly Stone last week (this article on their simultaneous loss is great)—two American treasures, if we can call them that. I’ve been hesitant to give the Beach Boys the moment they deserve because they have so much music. But here I go! I cannot stop listening to Surf’s Up, which is, somehow, the band’s 17th album? “Disney Girls (1957)” is the best and weirdest song I’ve heard in a long time; “‘Til I Die’” is a masterpiece; “Feel Flows” is perfect. A no-skip record among, I can only assume, a discography of no-skip records. We are lucky to have this music.

5. There’s a Riot Goin’ On by Sly & The Family Stone

Released the same year as Surf’s Up, and alluded to (by coincidence, I’m sure) on Surf’s Up in the track “Student Demonstration Time,” this is inarguably the best Sly Stone album. I’m in from the first track. “Runnin’ Away” is my favorite song, but “Just Like a Baby” is a close second. Another album we’re lucky to have.

6. “Laurels” by Pelvis Wrestley

I’ve heard “Laurels” dozens of times, many of them live and once at out wedding last summer. But sometimes a song snags your brain in exactly the right way and tears you open anew. Right now, I’m so enamored with this lyric from the chorus, “Got a wagon and a wheel and a heart for the world.”

That’s kind of it? A wagon and a wheel and a heart for the world. Don’t forget about that.

‘Til next time.